Legislation Information

Pending Legislation

PA's Electronic Bill Room

Type in the word "equine" in the search box to locate bills, (proposed legislation) relating to horses.

Federal Laws

Proposed regs will legalize every inhumane practice identified in the transport of horses to slaughter!

Doubles will be legal for 5 years AFTER the proposed regs go into effect. It has already been 4 1/2 years, that makes for 10 years of the continued use of doubles after this legislation passed..

EPN's Comments

on Proposed Regulations For the 1996 Commercial Transportation of Horses To Slaughter Act

CA Equine Council's

Comments on the Proposed Regulations For the 1996 Commercial Transportation of Horses To Slaughter Act

State Laws

Proposition 6,

The PROHIBITION of Horse Slaughter and Sale of Horsemeat for Human Consumption Act Of 1998, Does Not Violate The Commerce Clause

Horsemeat Laws

1996 Commercial Transportation Of Horses To Slaughter Act

December 7, 2001

Final Rule Commercial Transportation of Horses to Slaughter Act

American Horse Council, American Horse Protection Association, & Humane Society of US

propose to legalize every inhumane practice identified in the transport of horses to slaughter & put the very people identified as the abusers, the "killer buyers" in charge of the horses!

Proposed Regulations For the 1996 Commercial Transportation of Horses To Slaughter Act

USDA Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service, APHIS

Approval of Livestock Facilities;

Interstate Movement of EIA Reactors

USDA Food Safety Inspection Service, FSIS, Regulations

Biological Residues in Horses;

Slaughter of Foaling Mares;

Slaughter of Sick Horses;

USDA APHIS Humane Slaughter Act

AZ Transport Law

CA Transport Law

CT Transport Law

MA Transport Law

MN Transport Law

NY Transport Law

Ag and Markets, Section 359-a

Horses inside double deck cattle trailer stopped by the NYSP. The owner was later convicted & fined $3000.00.

VA Transport Law

Vermont Transport Law

PA Anti Cruelty Law

Title 18, Section 5511

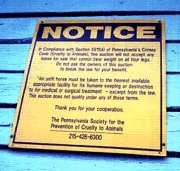

Sign Posted at PA Horse Auctions is NOT the Law!

Sign outside auctions is incorrect!

Sign posted outside 2 PA horse auctions regarding the PA Anti Cruelty Statute is incorrect! " Maybe the posting of this sign has something to do with "the agreement" that the auctions and the PA SPCA have with each other...

U.S. Anti-Cruelty Statutes

PA Domestic Animal Act

Licensing of Dealers & Haulers

EIA Regulations, Coggins Test

PA Dead Animal Act

Requirements for Removal of Dead Animals

PA Animal Markets

General Provisions

Records

Transactions From Trucks

IL Horsemeat Act

Texas Law

Sale of Horsemeat for Human Consumption

Prohibits Sale of Horsemeat For Human Consumption

Texas Attorney General Cornyn States TX Law

Prohibiting Sale of Horsemeat Applies to the 2 Texas Horse Slaughterhouses!

Links

California Voters "Just Say Neigh" to Horse Slaughter!

HoofPAC

Shop online at IGive.com with over 400 great stores you know & love- including Back In the Saddle! Up to 26% of the purchase price is donated to the EPN!

The EPN gets $5 extra the first time you shop!

PayPal accepts credit cards! Please send your tax deductible donation to the:Equine Protection Network, Inc.,

P. O. Box 232, Friedensburg, PA, 17933.

Shop for CD's at CDRush.com & the EPN Benefits!

Put "EPN" in the Coupon Code box when you place your order.

Now you can save money on your favorite music and help the horses at the same time!

HoofPAC is the political action committee that has been formed to end the slaughter of America's horses. Cathleen Doyle, founder of HoofPAC, led the successful Save The Horses campaign in 1998 that made the slaughter of California's horses a felony.

CA Equine Council Comments On Proposed Horse Transport Regulations

This letter is posted with permission from the CA Equine Council.

Please contact your US Senators and US Representatives regarding the proposed regulations for the Commercial Transportation of Horses To Slaughter Act.

These comments may be passed along to your legislators.

To locate your US Senator & US Represenative call: 202-224-3121.

Or go to Vote Smart .

Law Offices of Lowell Finley

1604 Solano Avenue

Berkeley, CA 94707

510/290-8823

510/526-5424 fax

Docket No. 98-074-1

Regulatory Analysis and Development

PPD

APHIS

Suite 3C03

4700 River Road Unit 118

Riverdale, MD 20737-1238.

Re: Docket #: 98-074-1

Title: Commercial Transportation of Equines to Slaughter

Docket Type: PRM

Publication Date: 5/19/99

CFR Part: 9 CFR 70, 88

FR Citation: 64 FR 27210

As we will demonstrate, the proposed regulations are seriously inadequate in the protection they afford to equines destined for slaughter and plainly inconsistent with the mandate given by Congress to the USDA in the 1996 Farm Bill.

1. Definitions. The accepted practice of federal administrative agencies when drafting regulations to implement a Congressional statute is to repeat the terms and definitions found in the authorizing statute, adding elaboration

where appropriate. Rather than follow this conventional approach, USDA rejects Congress’ terms and definitions in favor of its own. In the process, USDA has radically and impermissibly narrowed the broad scope of coverage

that Congress intended when it authorized regulations on the commercial transport of equines to slaughter.

The key operative terms defined in the statute are “slaughter facility” and “person.” Rather than base its proposed regulations on these terms as defined by Congress, USDA has made up its own operative terms --

“slaughtering facility” “owner,” and “shipper” -- and defined them in a manner that distorts Congress’ intent. The following table compares the terms and definitions in the statute (left column) with the terms and definitions in the proposed regulations (right column):

STATUTE

“Slaughter facility, including an assembly point, feedlot, or stockyard.”

PROPOSED REGULATIONS

“Slaughtering facility. A commercial establishment that slaughters equines for any purpose.”

STATUTE

________________________________

“Person. – The term ‘person’ –

(A) means any individual, partnership, corporation, or cooperative association that regularly engages in the commercial transportation of equine for slaughter; but

“(B) does not include any individual or other entity referred to in subparagraph (A) that occasionally transports equine for slaughter incidental to the principal activity of the individual or other entity in production agriculture.”

PROPOSED REGULATIONS

_______________________________

“Owner. Any individual, partnership, corporation, or cooperative association that purchases equines for the purpose of sale to a slaughtering facility.”

“Shipper. Any individual, partnership, corporation, or cooperative association that engages in the commercial transportation of equines to slaughtering facilities more than once a year, except any individual or other entity that

transports equines to slaughtering facilities incidental to the principal activity of production agriculture.”

__________________________________

In the shift from Congress’ term “slaughter facility” to the proposed regulations’ term “slaughtering facility,” the scope of regulatory coverage shrinks. Under the proposed regulations, only transportation to the actual

“establishment that slaughters equines” is covered. Transportation to assembly points, feedlots, and stockyards, included in Congress’ broader term, is not covered . As a result, the proposed regulations neglect these important phases of the process.

Similarly, in the course of replacing the statute’s single term “person” with the two terms in the proposed regulations, “owner” and “shipper,” the proposed regulations manage to exempt from coverage entire classes of

(1) horse owners who do not fit the regulations’ narrow definition of “owner” and (2) horse transporters who do not fit their definition of “shipper,” even though Congress meant for them to be covered as “persons” under the

statute’s definition. Congress included in the definition of “person” any individual or entity “that regularly engages in the transportation of equine for slaughter,” exempting only those who “occasionally” transport equines to

slaughter “incidental to the principal activity of the [same] individual or other entity in production agriculture.” But “owner” as defined in the regulations includes only an individual or entity “that purchases equines for the purpose

of sale to a slaughtering facility.” (Emphasis added.) And in defining the new term “shipper,” the proposed regulations appear to track the statute by exempting transportation that is incidental to the principal activity of

production agriculture. However, the proposed regulations drop Congress’ requirement that production agriculture be the principal activity of the individual or entity doing the transporting if an exemption is to apply.

The combined effect of these changes is dramatically illustrated by applying the proposed regulations to foals of “Premarin” horses. The proposed regulations would ban transportation to slaughter of foals under six months of

age – unless the exemption applies. Hundreds of farms in the U.S. and Canada keep tens of thousands of mares pregnant to harvest their urine for use in the manufacture of “Premarin” -- short for “pregnant mare urine” -- a

female hormone replacement drug. Many of the foals born to the pregnant mares as a by-product of this business are currently transported to slaughter before reaching the age of six months, either by buyers who purchase the

foals at auction or by the horse farmers themselves. If the proposed regulations applied to those who own and ship these foals, such transport would be banned. If they are exempt, it could continue.

If the agency had adhered to Congress’ definitions, Premarin foals would not be exempted from the regulations’ ban. Under Congress’ definition of the term “person,” a Premarin farmer who makes several shipments of

Premarin foals to slaughter facilities would not be exempt. While the shipments would be incidental to the farmer’s primary activity of production agriculture, they would not qualify as “occasional.” Similarly, a trucking company that transported several shipments of Premarin foals to slaughter would not be exempt under Congress’ definition, because the trucking company is not itself engaged in production agriculture as its primary activity.

But the agency has not used Congress’ definitions. Under the agency’s proposed definitions, a Premarin farmer who ships his own foals to slaughter is not an “owner,” because the farmer did not purchase the foals, or any other

equines, for the purpose of sale to a slaughtering facility. The farmer is also not a “shipper,” because his transportation of the foals to slaughter is incidental to the principal activity of production agriculture. Thus, a Premarin farmer driving his own foals to slaughter is completely exempt from the proposed regulations. And, if the farmer instead contracts with a commercial trucker to transport the foals, the result is the same: no one is covered

by the regulations. As explained above, the farmer is not an “owner.” The trucker is not an owner, either, nor is the trucker a “shipper” under the regulations because – due to the definitional sleight of hand discussed earlier in these comments – the transport is incidental to someone’s primary activity of production activity (the farmer’s), even though that is not the trucker’s primary activity. The result: neither the farmer or the trucker is subject to the regulations as written, and there will be nothing as far as the federal government is concerned to prevent the transport of these foals under six months of age to slaughter.

This is a loophole big enough to drive many trucks through, and not just trucks loaded with Premarin foals. The proposed definitions would exempt all professional horse breeders and the trucking firms that transport their

unwanted foals to slaughter. It is common for the mares owned by a single breeder to bear dozens, even hundreds of foals per year, only a small percentage of which are sold into non-slaughter markets (for racing, show, and other purposes). The rest are often transported to slaughter plants, where they will fetch the breeder hundreds of dollars apiece. This gaping loophole for unregulated mistreatment of young foals is not what Congress intended and it must be corrected.

2. Preemptive effect. The proposed rule fails to “specif[y] in clear language the preemptive effect, if any, to be given to the regulation” (emphasis added), as required by Executive Order 12988. Section 88.2(a) of the proposed

regulation provides in general terms that “State governments may enact and enforce regulations that are consistent with or that are more stringent than the regulations in this part.” The Notice of Proposed Rulemaking states, however, that, if adopted, “[a]ll State and local laws and regulations that are in conflict with this rule will be preempted.” 64 Fed. Reg. 27219. This generic restatement of the principle of federal preemption “specifies” nothing.

Indeed, the statement concerning preemption in the Notice is difficult to reconcile with the language in the proposed regulations permitting “more stringent” State regulations. To illustrate the problem, the Notice

statement on preemption and the language of the regulation can be applied to the provision in the proposed regulations that would permit, for five years, continued used of double-deck trailers to transport equines to slaughter, a practice which several States currently prohibit. Will these existing State regulations be deemed “in conflict” with and therefore preempted by the proposed federal regulation because they prohibit what the federal

regulation allows? Or will the State regulations continue to be valid because they are “more stringent” than the proposed federal regulations? It is clear from the text of the statute and the Conference Report that Congress

had no intention of entirely “occupying the field” of regulation in this area to the exclusion of state regulation. Accordingly, the regulations should specifically state that state regulations prohibiting conduct the federal

regulations would allow are not preempted unless compliance with the state regulations would make compliance with the federal regulations impossible. Unless this issue is clarified in the regulation itself, adoption of the

proposed regulations is likely to generate the “needless litigation” that Executive Order 12988 sought to avoid by its requirement for specific, clear language on preemptive effect.

3. Standards for conveyances. Section 88.3 of the proposed regulations would prohibit use of double-deck trucks to transport equines to slaughter. However, as noted above, an exception would permit for five years

following publication of the final rule continued use of double-deck trucks that lack the capability to convert to one level. This exception is squarely inconsistent with the recognition elsewhere in the regulation of the necessity to provide “sufficient interior height to allow each equine on the conveyance to stand with its head extended to the fullest normal postural height.” It is also squarely inconsistent with findings from the research mandated by

Congress. The agency acknowledges as much in summarizing the results of the research: “[W]e do not believe that equines can be safely and humanely transported on a conveyance that has an animal cargo space divided into

two or more stacked levels.” 64 Fed. Reg. 27213.

The justification offered for the five-year exception – “to ease the burden of this proposed regulation on the affected entities” – cannot withstand scrutiny. First, contrary to the characterization of this exception in the Notice

as a “grandfather clause,” the proposed five-year grace period is not limited to double-deck trailers that are currently being used to transport equines. As written, a shipper in the business of transporting horses to slaughter

could at any time during the five-year period begin to use a new double-deck trailer, or a double-deck trailer previously used to transport non-equine livestock. Second, the exception appears to be based on the unsupported

assumption that immediate prohibition of the ban on use of double-deck trailers currently being used to transport horses to slaughter would impose an economic hardship on their owners by eliminating all economic use. This

assumption is false because double-deck livestock trailers are designed and intended for transporting non-equine livestock, such as cattle and sheep. Owners can therefore recover their investments in non-convertible

double-deck trailers by shifting their use to transport of non-equine livestock, or by selling or leasing the trailers to others for such use. Again, the agency acknowledges as much in the Notice, as follows:

[T]he proposed ban on transporting slaughter equines in conveyances divided into more than one stacked level should not impose a burden on the owners of double-deck trailers because these trailers can be, and are, also used

to transport other commodities, including livestock other than equines and produce. In fact, it is estimated that double-deck trailers in general carry equines no more than about 10 percent of the time they are in use. If the

proposed ban takes effect, commercial shippers who transport equines to slaughtering facilities should be able to use their double-deck trailers to transport other livestock and produce. Owners who use their own double-deck trailers to transport equines to slaughtering facilities would have to find another use for the equipment or trade for single-deck trailers. This situation should not pose a problem. Owners should be able to sell their serviceable trailers at fair market vale to transporters of commodities other than equines. 64 Fed. Reg. 27218.

4. Requirements for transport. Several rules in his segment of the proposed regulations are inconsistent with the findings of the USDA-commissioned research on which Congress intended the regulations to be based. First,

the proposed regulations would not, “[f]or practical reasons,” “regulate the care of equines destined for slaughter prior to loading on the conveyance for shipment to the slaughtering facility,” even though they would require

owners to certify in writing that their horses are fit for travel. 64 Fed. Reg. 27211. Oddly, the agency justifies this decision by arguing “research has shown that the vast majority of injuries caused to equines in transit to slaughter occur when the equines are actually in transit or during loading or unloading.” This, of course, begs the question: if there is a pattern of equines unfit for travel due to pre-existing injuries or infirmities nevertheless being

transported for slaughter, research on “injuries caused to equines in transit” will not reveal it. And, according to other research commissioned by the USDA specifically for the development of these regulations, research the

agency disregards on this point, there is a very real pattern of such pre-existing injuries and infirmities.

The results of one of the studies commissioned by USDA/APHIS for this rulemaking are reported in an article entitled “Survey of Trucking Practices and Injury to Slaughter Horses.” The article is co-authored by Temple

Grandin, Kasie McGee and Jennifer Lanier of the Department of Animal Sciences at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, Colorado. The authors observed 63 trailer loads carrying a total of 1008 horses arriving at two

slaughter plants in Texas in July and August of 1998. Among their conclusions are the following:

The greatest welfare problems observed in this survey were caused by either neglect or abuse at the point of origin. Six percent of the horses surveyed had serious welfare problems that occurred at the point of origin and 1.8% had severe welfare problems caused by injuries which occurred during marketing or transport.

. . .

Transport and market damage includes, but is not limited to abrasions on withers, back and croup scrapes, lacerations and abrasions on the head, fresh cuts, bite marks, and eye injuries.

Owner problems include, but are not limited to emaciated, severe founder, broken legs, bowed tendons, extensive infections, foot bent over, deformities, and tumors all over the body.

. . .

Approximately 73% of the severe welfare problems observed at the slaughter plants did not occur during transport or marketing. Some examples of severe welfare problems which were caused by the owner were severely

foundered feet, emaciated, skinny, weak horses, animals which had become non-ambulatory and injuries to the legs such as bowed tendons. Four horses were loaded with broken legs. One of these horses was a bucking bronc that

had broken its leg during a rodeo. It died shortly after arrival at a plant.

See also Grandin T, McGee K, Lanier JL, “Prevalence of severe welfare problems in horses that arrive at slaughter plants,” J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1999 May 15; 214(10):1531-3. The Notice makes no mention of these

findings, which cannot be reconcile with the agency’s decision not to regulate pre-loading care of slaughter horses, its decision to trust owners to truthfully certify that horses loaded onto trucks for slaughter are fit to travel, and its

decision not to require pre-transport inspection of slaughter horses by a veterinarian.

The second point on which the proposed “requirements for transport” are inconsistent with the findings of USDA/APHIS commissioned research -- and with well-established equine industry standards – is the maximum time

an equine can humanely endure without water, food, and rest. The proposed regulations would permit equines to be kept on trucks for up to 28 hours without water, food, or rest. The Notice asserts that “research has shown that

equines that have been provided [water, food, and opportunity to rest for at least 6 hours prior to being loaded] can be transported for at least 28 hours with no adverse health effects.” In fact, however, one of the studies

commissioned by USDA/APHIS for these regulations concluded that “[t]rips longer than 27 hours showed significantly greater changes over shorter durations in % weight loss, WBC, total protein, and lactate” – all

considered to be reliable stress indices. The study involved nine loads totaling 306 mature horses transported under hot and humid conditions from 370 to 1550 miles in trips lasting from 5 3/4 to 30 hours. The author, a

professor of veterinary medicine at the University of California, Davis, also found that “[i]n all loads, injuries increased with duration over 27 hours . . . .” Carolyn L. Stull, Ph.D., “Stress and Injuries in Horses Commercially

Transported to Slaughter in the U.S.,” emphasis added. It is also noteworthy that the same researcher, when not being funded specifically to study slaughter horses, recently concluded that “[t]ransportation in hot, humid

conditions should attempt to minimize thermal stress by carefully selecting departure/arrival time schedules to avoid the hottest portion of the day, frequently offering (every 4-6 hours) water to the horses, and limiting the

duration of the trip.” Carolyn L. Stull, Ph.D., “Physiology, Balance, and Management of Horses During Transportation,” Proceedings of the Horse Breeders and Owners Conference, Red Deer, Alberta, Canada, Jan.

10-12, 1997, emphasis added.

The other researcher funded by USDA/APHIS, Ted Friend of the Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Texas A&M University, concluded that tame horses in good condition and initially

deprived of access of water for approximately 6 hours can be transported for up to 24 hours before dehydration and fatigue become severe. It should be noted, however, that the study was terminated after 24 hours of transport

because 3 of the 30 horses were deemed unable to continue. Friend TH, et al., “Stress response of horses during a long period of transport in a commercial truck,” J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1998 Mar. 15;212(6):838-44. And the same researcher, when interviewed about his research, stated flatly: “If you have to haul horses more than 24 hours, then the truck must be equipped with a watering device.” Herbert KS, “Searching For A Good Ride:

Research on transporting horses to slaughter,” The Horse: Your Guide to Equine Health Care 1997 Oct.;14(10):66-68. The proposed regulations contain no requirement for such watering devices.

Neither study directly supports the 28-hour limit on which the agency settled. Perhaps it is merely coincidence, but 28 hours is also the limit Congress placed on rail transport of all livestock, including cattle, sheep, and swine, 93

years ago, without the benefit of modern scientific research. See Stat. 607, ch. 3594, Sec. 104 (June 29, 1906), amended and re-enacted by Pub. L. 103-272, Sec. 1(e), July 5, 1994, 108 Stat. 1356 and codified at 49 U.S.C. sec.

80502.

Other recent research has also shown serious adverse health effects from travel for periods well under 28 hours. See, e.g., Oikawa M, et al., “Pathology of equine respiratory disease occurring in association with transport,” J.

Comp. Pathol. 1995 Jul;113(1):29-43, which reports that three of eight young thoroughbreds showed clinical respiratory abnormalities after 20 hours of transportation by truck. In July of 1999, a group of eight internationally-renowned veterinarians and researchers who had advised on care of horses competing in the hot and humid conditions of the 1996 Atlanta Summer Olympics announced that they will within months release a set of

guidelines on horse transport, to be published in book form by the American Horse Shows Association. In a recent roundtable discussion published in the July, 1999 issue of The Horse: Your Guide to Equine Health Care, the eight

gave their views on, among other things, the adverse effects of extended travel on equine respiratory health, and how frequently horses need access to water during transport. Excerpts follow (emphasis added):

It is very clear that transportation is associated with the onset of respiratory disease in some horses. In an epidemiological investigation conducted by the University of Illinois, transportation for greater than 500 miles was

the greatest risk factor for development of pleuropneumonia. Investigators in Japan have also shown that transportation for more than 20 hours is associated with the onset of fever and pneumonia. [N. Edward Robinson,

BVETMED, PhD, MRCVS, Docteur Honoris Causa (Liege), Matilda R. Wilson Professor of Large Animal Clinical Sciences, Michigan State University College of Veterinary Medicine.]

. . .

Transit-associated respiratory disease is a major problem in transporting horses. The mean incidence of the disease in racehorses belonging to the Japan Racing Association that were shipped below 1,000 km between 1993

and 1997 was 1.2%. Otherwise, in cases involving prolonged transport by road of over 1,000 km between 1989 and 1994, the incidence was 11.9%. These differences of values suggest an increased incidence of disease with

increased transport distance and/or traveling time. [Masa-aki Oikawa, DVM, PhD, Vice-Director, Equine Research Institute, Japan Racing Association.]

. . .

Water the horses every six to eight hours, and water intake should be monitored. . . . I have yet to see fluid or electrolyte deficits in transported horses unless they have become ill, provided they have been offered food and

water every six to eight hours. I’ve seen no evidence of dehydration. [Desmond Leadon, MA, MVB, Msc, FRCVS, RCVS, head clinician, Pathology Unit, Irish Equine Center.]

. . .

Taking steps to ensure that the horse maintains hydration is also important. Fluid loss can be substantial (up to

0.5% of body weight per hour). So, over a 12-hour period, the average-sized horse may lose 20kg or more as sweat and other “insensible” fluid losses. Horses need access to water on a regular basis during transport (at least every four to six hours). [Ray Geor, DVM, President, Association of Equine Sports Medicine.]

No final rulemaking should be conducted until the glaring discrepancies between the agency’s proposals and its own research findings have been addressed and serious consideration has been given to the forthcoming

international guidelines on horse transport.

Respectfully submitted,

LAW OFFICES OF LOWELL FINLEY

_________________________

Lowell Finley

Attorney for the California Equine Council/Save The Horses

Save America's Horses! |

|||||||

|

Please send your tax deductible donation to: Equine Protection Network, Inc., P. O. Box 232, Friedensburg, PA, 17933 |

||

Save America's Horses- Make the Commitment to Your Horse! |

||

|

Photos On This Page CANNOT be Used Without Written Permission

|

||